There are many historical moments that stand out in the timeline of Ghana’s anti-colonial struggle. 1947, 1950, 1951, 1954, 1956, 1957, 1960 and so on, you name them. But the year that had been the most consequential in my opinion, is often missing in the roll call – the year 1948. That year had been the most consequential not only because of the Accra riots but more importantly, its aftermath. It was a dialectical moment that not only birthed the critical mass for the independence movement but also determined the trajectory and outcome of it. Circumstances in 1948 drew a line in the sand between the ‘Veranda boys’ and the bourgeois Gold Coast lawyers and intelligentsia. That contradiction and sometimes hostility shaped the contours of the struggle and continue to define political relations in the country till today. However, proponents of the Danquah-Busia-Dombo and Nkrumahist traditions as well as those in between, make very little reference to 1948 in the never ending ideological and historical debates pertaining to the founding of Ghana. With a few days to close August, this article relies on the social uprising of 1948 the recent emotional outburst of President Akuffo Addo’s in his address on 4th August 2024. His argument basically sought to reduce the significance of Kwame Nkrumah and introduce his ancestors as founders of Ghana, through the back door of history.

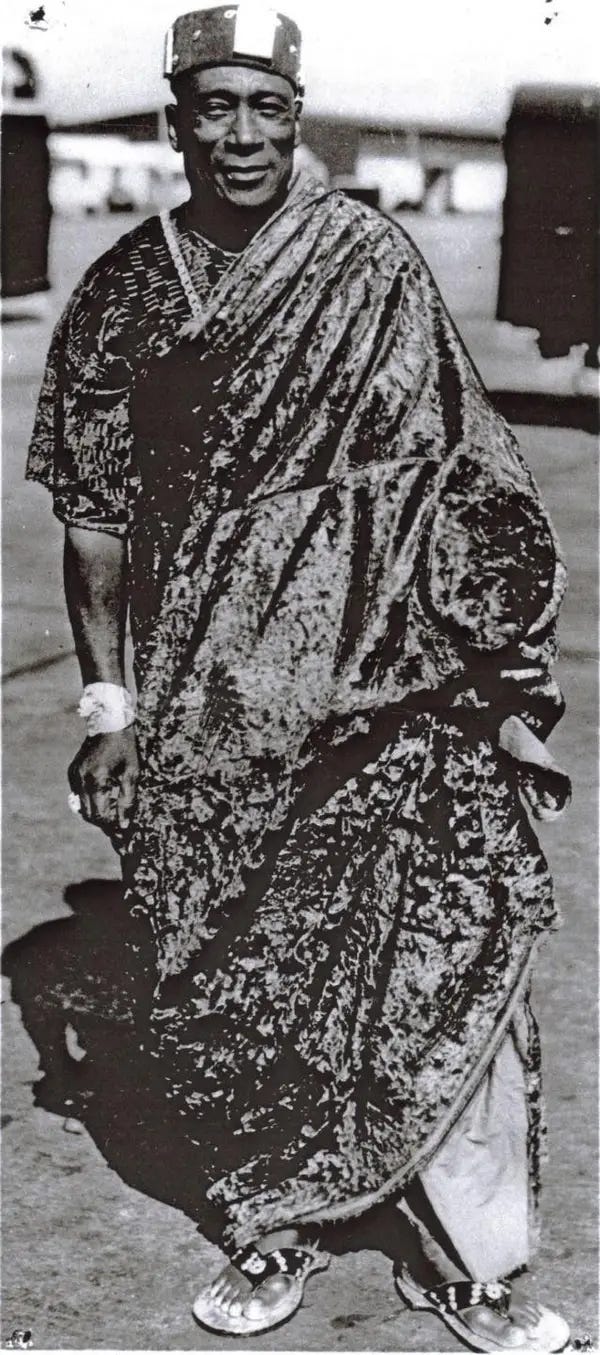

Kwame Nkrumah had barely settled in his new role as the general secretary of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), when Nii Kwabena Bonne, a sub-chief of the Ga state, organized a countrywide boycott of European and Syrian merchants on the account of the exorbitant prices they charged for their goods. Though latter-day historians would want us to believe that Nkrumah had something to do with the February 1948 disturbances, the fact of the matter is that he had nothing to do with it. Nkrumah was spending some time with his mother in Tarkwa when news of the Accra boycott reached him. Nii Kwabene Bonne and his supporters had never been members of the UGCC, but because the timing of the boycotts coincided with Nkrumah’s appointment in the UGCC, many perceived Nkrumah to be the instigator.

On 28th February, 1948, Nii Bonne called off the boycott campaign. But on the same day, as fate will determine, the ex-servicemen (Ghanaian veterans who had fought on the side of Britian in World War II) decided to hit the streets to push home their demands, which their former employer had completely disregarded. The two events were unconnected, though the timing might suggest otherwise. Here, unlike Nii Bonne’s boycott campaign, Nkrumah was aware of the grievances of the ex-servicemen, and their intention to protest. He tried organizing the ex-servicemen Union as an arm of the UGCC. However, it would be ahistorical for anyone to say as a matter of certainty that Nkrumah in his personal capacity or under the auspices of the UGCC, had urged them to protest. Whatever the grievances of the ex-servicemen were, they existed before Nkrumah came back or UGCC became a powerful political force in the colony.

Trouble began when the ex-servicemen reached the Crossroads towards Christiansburg Castle – the seat of the colonial governor. As they approached the Castle, the police ordered them to stop their advance, but the brave former soldiers would have none of it. They wanted to present their petition to the governor himself. The European police officer in command fired his gun and ordered his men to do same. The ensuing melee resulted in the instant murder of three ex-servicemen and the injury of five others. News of the clash reached town and almost immediately Accra went up in rage. Already, there was pent-up anger among Accra residents owing to the refusal of European and Syrian merchant to lower their prices, as part of the terms for calling off the Nii Bonne boycott. Ghanaians started beating up European and Syrian merchants. Riots, looting and burning of foreign properties including large stores and buildings continued for days. In the end, 29 people died and 237 sustained injuries.

The aftermath of these important historical incidents of 1948 would redefine the nascent struggle for Gold Coast independence in ways that were hitherto, unimaginable. The British colonial administration spared no time finding scapegoats. They needed to set an example out of those they thought were responsible so that they can douse the fire of emancipation and reverse the momentum that nationalism had began to build. The prime suspects here were Kwame Nkrumah and members of the Working Committee (From now on, WC) of the UGCC, later to be known as the ‘Big Six’. Nkrumah evaded arrest after rumors reached him of a bench warrant issued for his arrest. Two Accra women supporters of the UGCC provided safe hiding place until he quietly eloped to Saltpond where later, a police search party would apprehend him at dawn.

The Police rounded up the suspect members of the Big Six namely, Ako Adjei, Akufo Addo, Obetsebi Lamptey, Ofori Atta and Danquah. Together with Kwame Nkrumah, the Big Six were airlifted from Accra to a Kumasi prison. It was in this prison that Danquah broke down in tears. For the astute lawyer that he was, he had never anticipated ending up in such a condition – a prison. Unbeknown to Danquah, putting a fight against British colonialism comes at a very high and unpleasant price. To be fair to Danquah and the others, they had not challenged British colonialism and never intended to do so, and hence did not deserve to be in prison. They were in prison on trumped up charges and suspicion of having had a hand in the 1948 disturbances. Nkrumah on the other hand, knew prison was just half the price to pay if one was truly committed to fighting against imperialism. Nkrumah was poised, even whilst in custody. He called for meeting among his colleagues to discuss the way forward and an alternative to the Burns constitution, which they opposed. But Nkrumah would realize the rest of his colleagues had lost interest. They blamed him for their predicament. Not even Ako Adjei was spared blame for his part in recommending Kwame Nkrumah. Unfortunately, it was in prison that Nkrumah found out he has become a lone ranger and that if Ghana were to become independent, it would dependent largely on the next steps he took.

A few days in prison was all it took to break the resolve of these men, who previously thought of themselves prepared enough to lead the people of Gold Coast into independence. This calls into question, their commitment and even the true intention behind the formation of the UGCC. The answers to this question lay bare, when we scrutinize the circumstances surrounding the founding of UGCC. The verdict of the Kibi ritual murder trial which condemn to death, three family relatives of Danquah had influenced him totally as to change his positive attitude towards the colonial administration. In 1944, relatives of Danquah gruesomely murdered the chief of Apedwa, Nana Akyea Mensah, who was at the palace to conduct final rites for the burial of the Nana Sir Ofori Atta I, paramount chief of Akim Abuakwa. There are conflicting narratives concerning the intention of the murder. Thought to be his son, it was alleged that relatives of the Nana Sir Ofori Atta wanted to get rid of Akyea Mensah so that they could have all the properties of the dead chief. However, the colonial government interpreted the gruesome murder as a ritual murder – the stupid custom of murdering innocent people to pacify and accompany a dead chief.

In the ensuing legal battle, J.B Danquah, being the legal representative of the Akim Abuakwa State, moved heavens and earth in attempt to get the accused acquitted. Alan Burns, the governor, however, was also committed to applying colonial laws to the letter. After losing the legal battle in the Gold Coast, Danquah tried using his ‘political connections’ to get the ruling overturned by the House of Commons. He almost succeeded for his London moves had moved the UK Secretary of State for Colonies to try to intervene in Danquah’s favor. The governor Burns threatened to resign in protest, forcing the Secretary of Colonies to back off from the matter. Danquah was now alone and had no choice than to refrain from frustrating the hands of justice. But Danquah will never forgive Alan Burns for this. He immediately withdrew his support for the Burns constitution, which he had previously supported. Before the ritual murder, on March 6, 1944 at the centenary celebration of British colonialism in the Gold Coast, Danquah remarked that ‘he would be the last to call for the terrific wish of self-government for the Gold Coast.’ In contrast, after the courts condemned his family relatives to death, he remarked, ‘If the white man will kill us, then the white man will go back to his country.’ He made those remarks at the inauguration of the UGCC in Saltpond, 1947.

It appears therefore that the intention for Danquah’s involvement with the UGCC was to extract personal vengeance of some sort from governor Alan Burns. By helping to form the UGCC, Danquah and his relatives expected to leverage their newfound positions of strength to bargain for more power in determining judicial and political matters within the colony. A look at the draft constitution of the UGCC revealed that the working committee intended to restrict themselves to the colony and Ashanti to a lesser degree. The Northern Territories and Trans Volta didn’t feature in their programs at all. It was the sole initiative of Nkrumah to include latter two territories into the organizational jurisdiction of the UGCC. Prior to the arrival of Nkrumah, the working committee had organized only 13 branches, however, all but a few were operational. In contrast, within six months of his stewardship, Nkrumah had set up 500 fully functional branches in the colony alone.

The three-day Kumasi prison stint was a blessing in disguise for Nkrumah. Had that not happened, Nkrumah would have been laboring in vain in the worst case, or in the best scenario, laboring for others to take advantage of, for their own selfish interest. Proceedings and findings of the Watson Commission set up by Alan Burns to investigate the 1948 riots buttresses the above point. Appearing before the commission, all members of the working committee except for Mr. S.E Ackah, denounced the program that Nkrumah had presented to them for the reorganization of the UGCC. Furthermore, the WC, convinced in the prejudice of the commission that Nkrumah was a communist, outrightly denied him. They went as far as reducing him to a mere employee of UGCC, therefore, they argued the Commission should spare them the liability for Nkrumah’s actions.

Allegation of Communism will shortly after, form the basis for attempts by the working committee to sack Nkrumah from the UGCC. Also, the WC were livid that Nkrumah established a new school – Ghana National College, to accommodate the students, from Adisadel, St. Augustine and Mfantsipim, who the British sacked for protesting the incarceration of the ‘Big Six’. The late Ghanaian math prodigy, professor Allotey, is an alumnus of Ghana National College. For these ‘crimes’, the WC offered to give Nkrumah 100 pounds to buy a one-way ticket to London to carry on from where he had left off. Under the pressure from the movement, they later toned down to a demotion from a general secretary to treasurer of the UGCC, which Nkrumah accepted in good faith.

The tension came to a head leading to Nkrumah’s resignation and the ultimate collapse of the UGCC. But before this, Nkrumah and others such as Kofi Baako, Kojo Botsio, Komla Gbedemah, and Dzenkle Dzewu had decided to form the Convention Peoples Party (CPP) from the Committee for Youth Organization (CYO). On 12th June, 1949 Nkrumah announced the birth of the CPP in the presence of some sixty thousand members and sympathizers. The CYO was a youth sub-formation which Nkrumah organized, that served as the youth wing of the UGCC, even though the WC had opposed its establishment.

Knowing very well that the CPP was the first stage failure of the political careers, the WC of the UGCC sough the arbitration of some noble men to mediate the impasse between them and Nkrumah. At the end of their investigation, the arbitrators recommended the reinstatement of Nkrumah to his former position of General Secretary with the CPP adopted, acting under the vanguard of the UGCC. The working committee would however vehemently oppose the proposition of their own arbitrators, even though Nkrumah welcomed it. Save George Grant, all members of the working committee resigned in protest.

Members of the UGCC in a special delegate conference held in July 1949 adopted the recommendation of the arbitrators and called for an election to replace the vacancies on the working committee of the UGCC. The ex-working committee would oppose this as well, fearing defeat in an election. They asked for reinstatement without election. The gridlock continued and two new arbitrators came in. This time, they recommendation Nkrumah’s reinstatement but the dissolution of the CPP. Difficult as it were, Nkrumah almost accepted this recommendation until he went outside the conference room. Before him was a mass of fifty-thousand people on the conference ground invoking him to resign and lead them. Nkrumah obeyed the masses and tendered in his resignation, hurriedly written on the back one supporter, amid cheers and jubilation.

CPP became fully fledged independent political party, the first of its kind in the Gold Coast, in fact. The UGCC and CPP presented two different political strategies for de-colonialization. The CPP presented a radical revolutionary vision of ‘self-government now’ to the Ghanaian. The UGCC on the hand, stuck to its conservative, reactionary and ambiguous vision of ‘self-government within the shortest possible time’. In other words, UGCC was content with whatever room that the white man had made available for them. It had never been the organization’s intention to wage a struggle for independence. But this also speak of a class of African bourgeois, who out of contempt for the lay man, have never identified with him and feel it is their divine right by virtue of their western education, class and wealth, to be the natural heir of the white man’s position, regardless of the opinion and wish of the greater majority of the people they so much want to lord over. But the people of the Gold Coast proved them wrong.

A test of popularity for both parties soon came in the form of the 1951 parliamentary elections. The result was a landslide victory for the CPP. Out of the total 38 seat up for grabs, CPP won 34. Nkrumah who contested the Accra Central seat from James Fort Prison, won with an unprecedented 98.5 per cent of the total votes cast – the highest margin of all winning candidates. In contrast, Danquah, member of the working committee and a staunch critic of Nkrumah, contested for his hometown seat of Abuakwa on the ticket of the UGCC, but lost miserably. He lost to a family relative who stood on the ticket of the CPP. UGCC’s poor showing in the election settled the dragging dispute. The influence of the working committee in Ghanaian politics slipped into oblivion and by the time of the second parliamentary elections in 1954, the UGCC was completely dead.

This is a story of how spontaneous and violent social reactions to economic exploitation and marginalization in the Gold Coast would expose the true intentions of those who just few months prior, had set out or claimed to fight for independence. Given what transpired, it is very perplexing that 75 years on, descendants of the failed working committee of the UGCC would seek to apportion a role for their ascendants in the fight for liberation. These lesser-known but important stories of 1948 support the position that Kwame Nkrumah is the Founder of the Republic of Ghana.